Intelligent content filtering

About symbolic and connectionist AI and how each approach could be applied for an ad blocking problem.

2020-02-27 00:00 +0000

How do you know what a cat is?

It is certainly something furry, four-legged with a head and tail. But so is a dog. And a mouse. It certainly is something that meows - but some cats do not meow, yet we still agree they are cats. We can even (hopefully) agree that in the picture above there are three cats, even though we see nine legs, do not hear any meows, and see completely different color patterns on each.

The point is this: it is surprisingly difficult to define most of every day things we take for granted. Back in 2017, a couple of researchers wrote a paper where they tried to define what a physical container is. That paper is 60 pages long. One can probably also write a definition of a cat in a similar fashion, but it would be:

- Hilarious

- Very labor intensive

- Not necessarily transferrable to definitions of other entities - like “chair”.

So how does this relate to content filtering and what I want to talk about today?

Defining a cat using a set of rules would be considered a “symbolic” approach to AI. Symbolic AI is a method most prominently used in the 90s, and it does have a lot of applications where it works fine.

However, for reasons described above, it does not really scale to a lot of real world concepts. Thus connectionism (in a form of Deep Learning) came along. In the connectionist world, there is no explicitly defined set of rules, rather there’s just a dataset of training examples and an optimization objective which an algorithm should accomplish on its own.

A connectionist’s cat is learned, not hard coded.

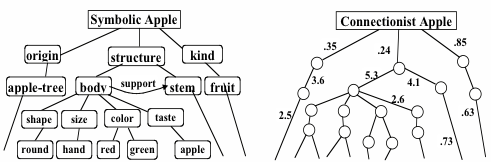

The concept of "apple" in symbolic and non-symbolic interpretations

Source: https://web.media.mit.edu/~minsky/papers/SymbolicVs.Connectionist.html

Implications for the Web

Most of the content filtering on the Web today is done using a set of rules (a.k.a filter lists). Even though those rules are rather simplistic for AI standards, it is reasonable to say that this is a symbolic AI. Knowledge is placed there, not learned.

Symbolic AI systems are also sometimes called “expert systems”, and I find it interesting to think about an ad blocker as an expert system.

As the Web evolves, ad blocking filters (rules) become more and more sophisticated and complex. They already went from simplistic rules like “hide elements that have feature X” to constructs like “hide elements which have property X, are nested within element Y with feature T and have a sibling Z with feature R”.

While this does still work in most cases, further evolution could be hard to maintain. On top of that, thanks to Adblock Plus and Acceptable Ads, recent developments of the Web push the advertising to be more subtle and merge with content even more.

Advertising can look like “recommended” items:

Recommended posts by Outbrain

or like content itself:

Native advertising by Mercedes-Benz in Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/brand-connect/mercedes/the-rise-of-the-superhuman/

It can also be in the form of Server Side Ad Insertion in media streams, sponsored messages in podcasts and YouTube, a paragraph in an otherwise interesting article, a logo on an image and more.

Some of these are already not addressable by content blockers - there is no language to write rules for those cases.

Developing software 2.0

So while an ad blocker as an expert system works, it explicitly tries to limit the scope of what it is. This is because, to list a few:

- The ad blocker only tries to block advertising, and nothing else

- it blocks the same things for everyone - different users, subscribed to same filter lists (expert system) would see the same things blocked

- it does not actually have a concept of an “ad” internally - it only works on proxy concepts. If a website or ad delivery method changes, it stops working until someone fixes it

- it constantly needs to increase the rule complexity. A constant game of cat and mouse with publishers who keep circumventing ad blockers causes this

All of these limitations make perfect sense, and even with them it is extremely challenging to implement an ad blocker properly.

But let’s just wonder for a second what would happen if we removed these restrictions? Yes, this could probably enable identifying advertising using much more subtle cues, but one thing for sure is that it will certainly increase the complexity of the whole ad blocking system. And that is assuming if it would be feasible at all.

Unless we go away with a concept of ad blocker as a symbolic (expert) system and consider an ad blocker as a connectionist system.

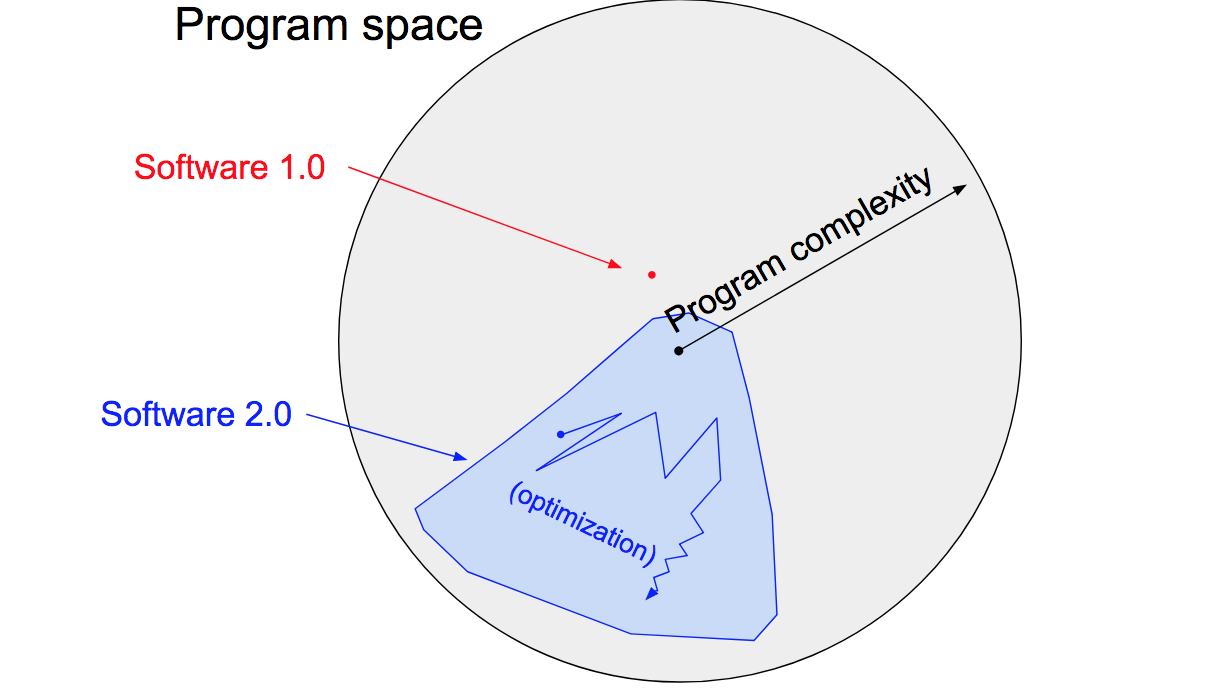

If we consider dropping explicit rules and rely on compiling datasets into models we would effectively arrive at a Software 2.0 implementation of a content filtering paradigm. Instead of a “simple” limited Software 1.0 system, we could have a much broader, and flexible, implementation in Software 2.0.

Illustration of Software 2.0 by Andrej Karpathy

Software 2.0 systems can implement much more complex systems, if only for a fact that in a way it is not humans who write them. A Software 2.0 system can “understand” what a cat is. Or what the article is about. Or if a specific element on a page was likely paid for (ie advertising).

Paul Graham, captured a similar sentiment in this old tweet:

How to get there?

Perhaps counter intuitively, real obstacles on a path to a more Software 2.0 content filtering is not a lack of research in machine learning and AI, or some exuberant costs for trainings needed. It is existing Software 1.0.

All of the Web is built around ideas of expert systems. Browsers expect you to provide a list of CSS rules to modify how they display things. With declarativeNetRequest you are also expected to provide a list of rules to decide which URLs to block.

As the Web matures, browsers take on more and more power over user’s online behavior. Since they were originally designed as “User Agents”, they try to provide some degree of control to their users, by implementing support for all these rules.

However would a real User Agent created in 2020 rely on rules to augment the user experience?

More importantly, what are the chances such a User Agent would be successful in serving the User’s interests when there are hundreds of models, trained on lots of user data, by big corporations trying to influence the User?

The movement to get the benefits of the AI transformation on the Web has already started, with tenslorflow.js, onnx.js, webdnn and other frameworks enabling machine learning models in browsers. W3C Machine Learning community group is also moving into the same direction, by trying to standardize on a fast and efficient way to run machine learning inference on the Web.

However merely enabling machine learning predictions is not enough, and a deeper transformation is likely needed. For example, maybe on top of supporting a list of CSS rules browsers could also support a list of machine learning models for augmenting the DOM? This is a change to the fabric of the Web, and WebKit/Safari has already started experimenting with this broader change with Intelligent Tracking Prevention.

But why stop at cookies and not apply the same kind of thinking to other areas of the Web? Perhaps with enough articulation from an ad blocking industry something like Intelligent Content Blocking can be standardized on? Hopefully a user will just need to decide on a provider.

Eating the elephant

It certainly is not obvious such a thing would be possible yet, but the only way forward I see is to try “eating an elephant one bite at a time”.

At eyeo we have already started using machine learning as a complimentary resource for our ad blocking expert system. However, following this path will likely be ineffective without a community-wide effort to change the inner workings of the Web. And that’s why it is better to start having discussions now.

Where are we going? What is our future? Is it useful to go beyond ads? Are we enabling content bubbles by allowing people to block specific content? How can we ensure adversarial robustness of such systems?

We may not need all the answers, but we need to have a joint understanding of the important questions.

I would like to leave you with perhaps the most important question of them all - do we want to enable users to block all the cats on the Web? Do we want CatBlock?

Let’s discuss!