Towards more intelligent ad blocking on the web

Ad blockers of today rely heavily on a community of filter authors, who are continuously adding, changing and removing the filters which…

2018-06-24 21:30 +0000

Ad blockers of today rely heavily on a community of filter authors, who are continuously adding, changing and removing the filters which define what is blocked or what is considered an ad. It is quite a laborious task, often requiring constantly visiting the same websites again and again, just to make sure the stuff that is supposed to be blocked gets blocked, and stuff that should not — doesn’t.

To alleviate some of the pain points of this process it would be useful to automate some routine parts, while keeping human authors doing what they do best — judging what constitutes an ad.

A recent arms race between Adblock Plus and Facebook prompted a research paper at Princeton, which suggested the concept of a “perceptual ad blocker.” And while Adblock Plus is still able to block Facebook ads today, the concept is interesting to explore. Here is a quote from the paper.

We rely on the key insight that ads are legally required to be clearly recognizable by humans. To make the method robust, we deliberately ignore all signals invisible to humans, including URLs and markup. Instead we consider visual and behavioral information

Another key insight comes from one of the most influential minds in Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning, Andrew Ng.

Since, generally speaking, a normal person can distinguish an ad from a non-ad in less than one second, it makes sense to explore how we can harness AI to help the filter list community.

To mimic the way humans see the web we’ll be looking at screenshots of websites, not actual code. The thinking is that whatever happens in the code, the end result is presented to a human user visually; so that’s where we should operate.

With that background, the problem becomes clearer. Given merely a screenshot of a website, identify where the ads on that screenshot are. If we are able to do that, then we’ll be able to automatically crawl the web, detect ads automatically on sites where such an approach is possible, and, in parallel, flag websites if they should be checked by human contributors.

This is known as an “object detection” task in the machine learning world. There are multiple algorithms to solve this, including:

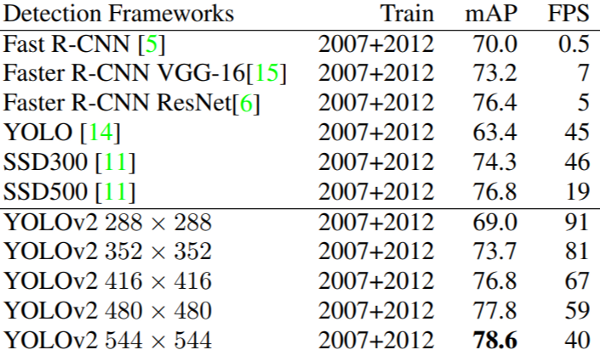

Source: YOLO9000 paper https://arxiv.org/pdf/1612.08242.pdf

Mean average precision (mAP) is generally agreed to be a good metric for performance of an object detection algorithm. There is a great explanation of what it is here, but essentially it is a metric of how closely predicted bounding boxes come to expected bounding boxes. Based on this metric, and the speed of inference, the updated versions of You Only Look Once (YOLO) are widely considered the most efficient object detection algorithms. That is why we decided to use YOLO in this case.

However, screenshots of web pages are very specific data, and it would be beneficial to the research to compare results of different algorithms on this specific task. The results of this will be released in follow up posts. We will also use different feature extractors in YOLOv2 implementation to get a better intuition on what different kinds of networks would learn.

As YOLO is a supervised machine learning algorithm, to train our model we would need a list of screenshots, annotated with bounding boxes for ads. Luckily, we can generate as many screenshots of websites as needed, and thanks to all the work of Easylist authors we can automatically generate the annotations too. As a proof-of-concept, we’ll be using the above mentioned ads on Facebook.

Source: https://getpayever.com/facebook-ads-for-beginners-guide/

Facebook ads are an example of native ads, and in this special case both the content and ads are controlled by the same entity. To get training data from Facebook we’ll implement a simple script that will instruct the browser to continuously scroll a Facebook feed, make screenshots and write annotations. Using a WebDriver API we can use the screenshot function to produce a training image, and getLocation to retrieve the element’s bounding box. Immediately a few caveats pop up:

- we have to be mindful about the screen resolution dpi, as browsers report element locations in native web page pixels, and screenshots are in end-user pixels.

- Facebook has to be continuously scrolled, meaning that the reported locations of elements must be adjusted by `window.pageYOffset`.

- Turns out Facebook is not endless!

The end of Facebook

One important thing to consider is that Facebook news feed ads look very much like regular entries, with very few distinguishing characteristics of their own. To make sure our neural network does not treat regular news feed entries as ads we have to show it examples of both ads and non-ads. So our script has to capture boxes of three classes:

- a news feed item,

- a news feed ad and

- a side ad to the right of the news feed.

After letting the script crawl Facebook for a few hours, we’ll end-up with a list of images and their annotations. However, because all of the screenshots are of the same size and ads are roughly in same location in each screenshot, we risk having the neural network overfitting to the location, rather than other ad features. We try to overcome that by running a script in a browser with different dimensions.

Implementing YOLOv2 from scratch is a pretty involved task, but luckily there are already implementations for various frameworks. For example, TensorFlow has a research section with object detection API built in. Nvidia DIGITS has a UI layer for object detection as well. Microsoft has just released an object detection extension for their Custom Vision API. For this exercise, however, for research purposes we will rely on another open source implementation of YOLOv2 for Keras.

For our implementation, the annotations are simple XML files, which are located in a separate directory from training screenshots. For proof of concept, we have produced a data set of 7948 screenshots. In the data set there are 15902 examples of a news feed item, 1502 examples of a news feed ad and 3494 examples of a side ad. We can then divide the data set into 3 groups — training, cross-validation and test set; approximately 80%, 10%, 10%, respectively. With this training set up we are achieving a 0.93 mAP score with YOLOv2 network with 608x608 input data. 0.9883 for news feed items, 0.9234 for news feed ads and 0.8919 for side ads. The scores are quite high, as the generated data is very homogenous. So in a way we are over-fitting to synthetic data, but it is fine for the defined task.

Such a set up produces fairly good recall, and we can identify where the objects are:

It also looks like we are able to figure out some features of ads vs non-ads, but more work in this area can certainly be done. It would also be interesting to compare the model performance with human reference, as Facebook ads are masked as native content.

For some intuition of what the model learned, here is a recorded video of the trained model performing inference (not real time):

Running inference on every frame

As expected, it looks like a full news feed item, with “Suggested post” on top is classified as an ad fairly reliably. It doesn’t look like the model has picked up on “Sponsored” text yet though. This is something we can focus for future research.

We have set out to train a model to detect Facebook ads. So far we have been training and evaluating on `synthetic` data, produced by a script scrolling the Facebook news feed. We got some fairly good results, but we also wanted to make sure our model can generalize well, so that what the model considers an ad would approximate very closely what people consider an ad. We thought it would be helpful to involve the community here. For that we have exported the trained Keras model to a saved TensorFlow model (.pb) and set up a TensorFlow Serving instance to serve it. We have also created a Facebook bot and wrapped it inside a Flask server, hosted using Gunicorn. The Bot accepts screenshots from users, prepares them for the TensorFlow graph and passes them to the TensorFlow Serving instance. We orchestrate our setup using docker-compose. All code is available here. We anticipate the Bot will not be as good on user submitted screenshot data, as it is inherently different in nature. And also, there are apparently 10 000 versions of Facebook on the Web. However we plan to retrain our model with a dataset of user submitted screenshots and make it better over time.

This is only preliminary research on possible uses of Machine Learning methods for making the Web better. While there’s a lot more to try, the approach described here can already help the filter list community. We can now set up an automated crawling process to go on pages and render them to see exactly what the user would see. Based on those renders we can make decisions if a human filter list author should check the page.